Ethics and Tech

We probably all know, to some degree or another, that our data is constantly being harvested by tech companies. Those companies track us across the web, and monetize the information they have on our browsing habits, selling our data to advertisers and other corporate interests. Some of this data is information we quasi-choose to give away (by having a facebook account, perhaps, or wearing a fitbit) but much is extracted from us without our knowledge. (Did you know that facebook can track you across the web even if you don’t have a facebook account, for example?) A particularly good example of data extraction – courtesy of hypervisible, our pedagogy expert at the Bright Institute last week – is that license plate readers are constantly recording where you’re driving. No one “consents” to have their license plates read just by driving down a public road. But our data is gathered regardless.

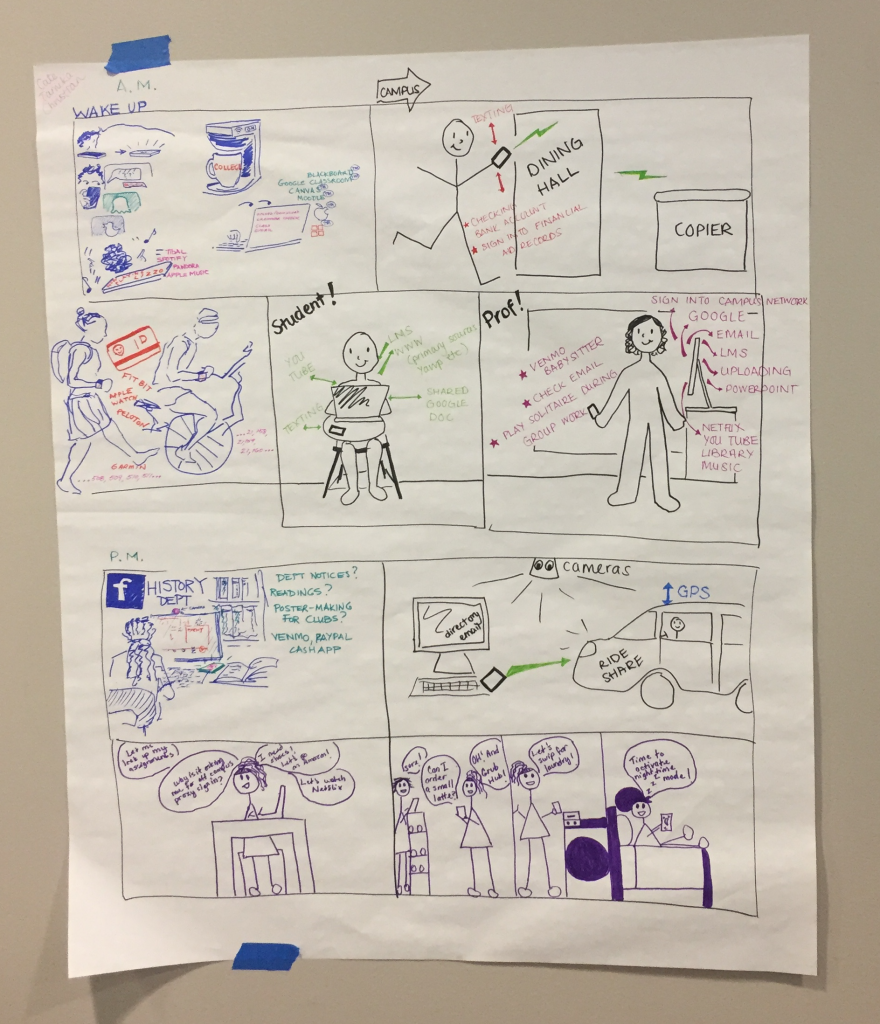

Similarly, huge amounts of data are extracted from our students as they go through their daily lives on our campuses. Last week, hypervisible asked us to consider all the data that a student might give away or have extracted from them on an average day on campus. Christian Crouch, Tamika Nunley, and myself drew this comic strip showing just some of the ways that happens.

As educators, we don’t have control over all the data students give away or have extracted. But there are places we can make a definite intervention.

First – most of us use a learning management system (LMS) like Blackboard, Canvas, or Google Classroom. These systems require students to log in to use them, which means their individual choices can be tracked – whether they download readings and assignments; how long they spend on a particular page; what their grades are; whether they were in class, and more. Students might write their papers within an LMS system (by using and connecting Google docs, for example), but all LMS systems can read the metadata on a document for how long a student spent actively working on the assignment. Some LMSs require students to submit papers through TurnItIn or Grammerly. All of this information is being monetized in some way or another. TurnItIn, for example, takes ownership of the intellectual property rights rooted in all papers fed through its system. Canvas is working to “predict” what a student’s grade will be in a class before they’ve so much as shown up, all based on their behaviors and grades in other classes. (This is sold as retention data, but it’s not hard to see the sinister underside to predicting a student’s grade before they’ve walked into our classroom.)

So what can we do to limit our students’ unwitting data exposure?

First, we can put a tech ethics statement in our syllabi. Here’s the statement I drafted last week:

Whenever we’re online, or logged into a learning management system like Moodle or Classroom, our digital identity is being tracked. We will therefore spend time learning how to make informed choices about our use of technology. I will also ensure that there are analog options for you throughout this course, so that you can minimize the extent to which your digital data is mined.

The first part of this statement requires me to help my students understand the stakes related to data collection and mining. Happily, many wise and smart people have made this a pretty easy thing to do. The University of Mary Washington has made a series of course modules on digital knowledge and skills available through its Domain of One’s Own program. There’s also a short, multi-part documentary series called Do Not Track which is easy to assign as homework (in pieces, or all at once). These provide excellent starting points for conversation with our students about what’s at stake when they log in or go online.

The second part asks me to make some alterations to the way I provide course information. I’m not going to stop using Google Classroom altogether, but I am going to offer alternate ways for students to get hold of class material if they want to limit data collection. My syllabus is usually written and hosted in Google Docs, for example, so I’ll simply make it possible for anyone with the link to the doc to find it without logging into the system. I’m going to print hard copies of the syllabus, also, and hard copies of all the assignments. I’m going to put an old-fashioned set of photocopied articles on reserve at the library in addition to linking to stable URLs of each article. I’ll accept paper copies of assignments instead of insisting they be turned in through Classroom, and I’ll store grades in a spreadsheet I create instead of using Classroom’s gradebook. These are pretty simple steps I can take to allow students to take my class “untracked.” I’m sure there are more steps I’m not thinking of right now, too.

It’s easy for some of us to throw up our hands and say “privacy is doomed, why bother?” But not all of us equally bear the weight of losing our digital privacy. Surveillance has a long and inglorious history in the United States, stretching back to first contact, where communities of color are more likely to be surveilled, with terrible consequences, than people who are white. The same is true for our digital lives. While it may be easy for some of us to hand wave privacy concerns, that is not a choice we should make on behalf of our students, especially our students of color, first-gen, and low-income students. Our students deserve information, guidance, and choices. I’m unendingly grateful to hypervisible for facilitating conversations in which this became so clear.

P.S. Think about changing your default search engine to Duck Duck Go, which doesn’t track you across the web.