Curiosity

If you, like the students in my undergraduate History Pedagogy course, are reading Josh Eyler’s How Humans Learn, you’ll know that curiosity is a human want that it’s worth harnessing if you want to be a good teacher. Want is perhaps too weak a word – Josh suggests that curiosity is a need, a hallmark of being human, and while children have it in spades, we get more distracted (or jaded?) as we grow older. The research suggests this is true about students as they move through middle and high school – good grades are rewarded where genuine curiosity is perhaps not– and isn’t always at the forefront of how or why people learn in college. But if you can create the circumstances for people to be curious, to use their instinct to wonder about the world to engage with your course, they’ll learn more and be more engaged. Josh provides lots of tangible examples of how to do this, and my students read the whole section for today’s class.

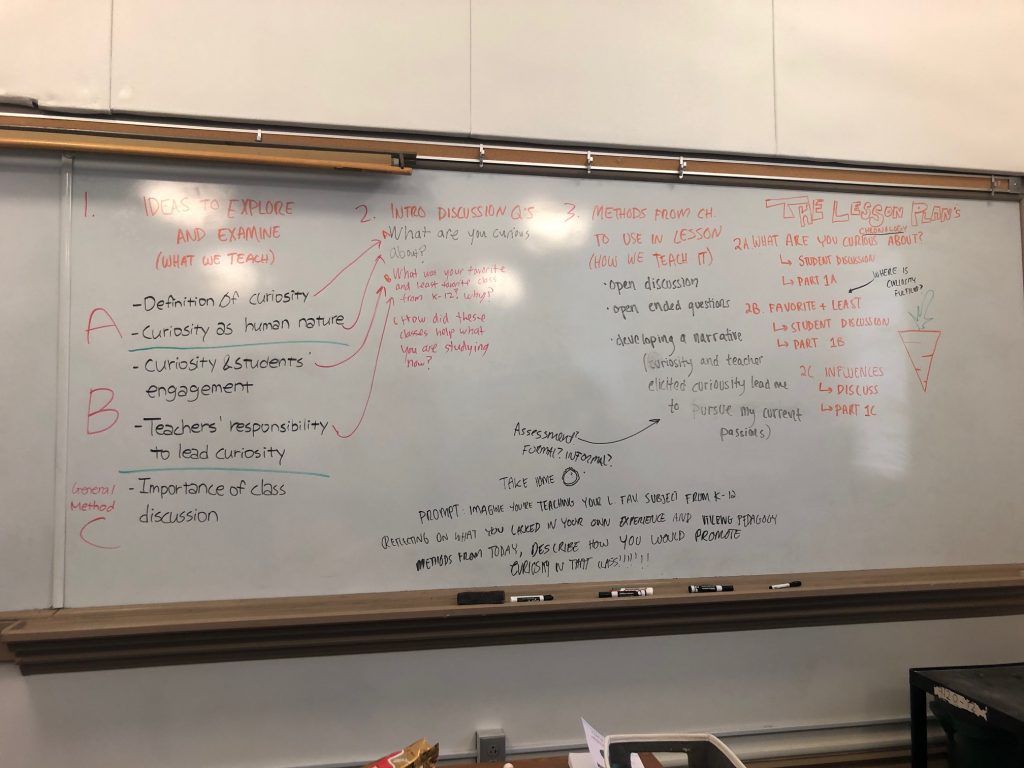

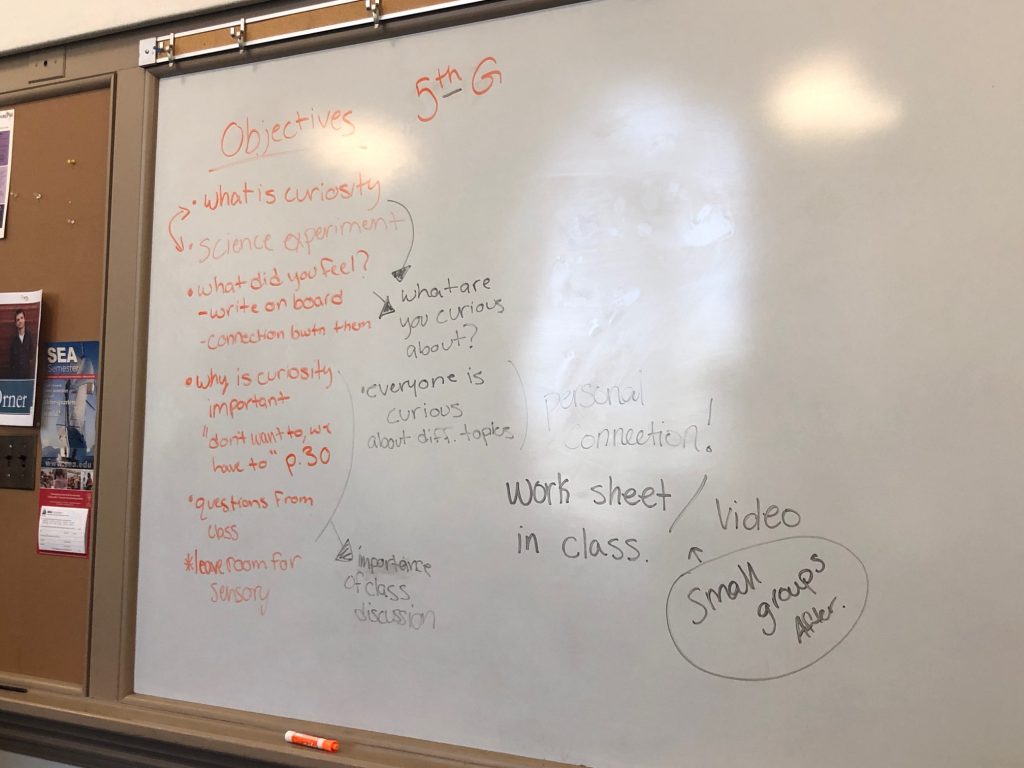

I could have had my students simply talk about what they read, and think about its application to teaching in conversation with one another. But that wouldn’t necessarily have harnessed their curiosity. So instead, I split the group into four smaller groups, and asked each group to come up with a lesson plan for teaching the day’s reading. I made markers, colored pencils, scissors, glue, paper, cardstock, and Legos available to everyone, too.

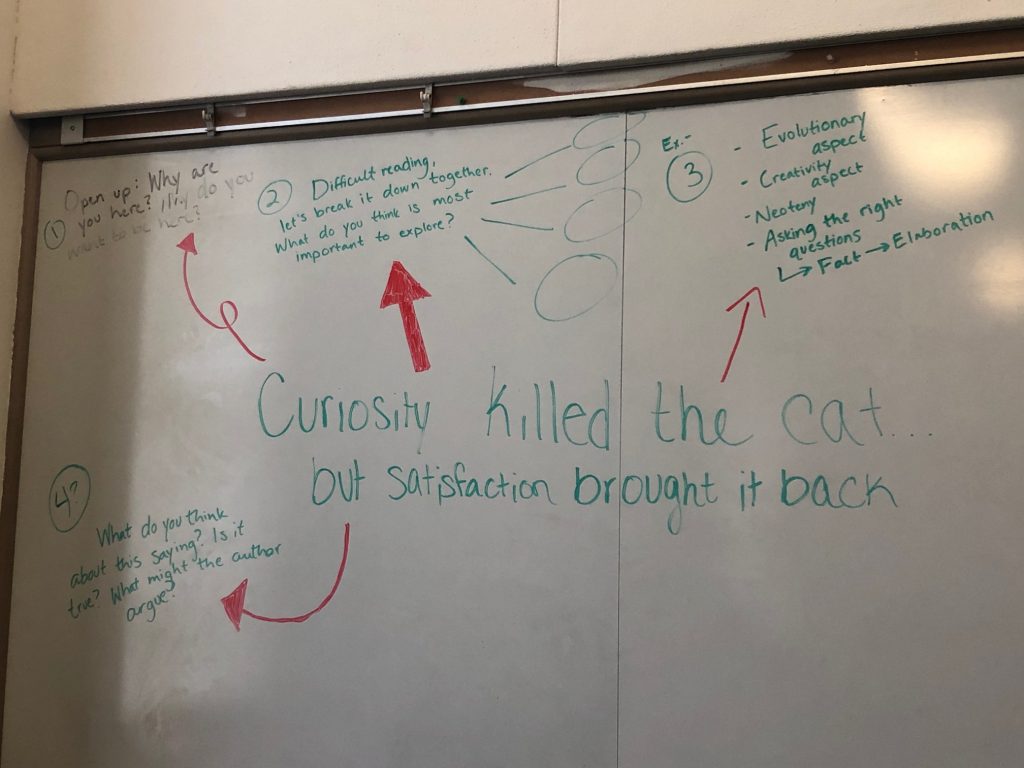

Despite being very distracted by the Legos at first, the groups soon dug into the material, and began brainstorming (some on computers, some on whiteboards). I wandered the room nudging the groups as I went. Had they talked about the elements of the reading they agreed upon? In one group: working with younger students on different weights and measures might harness their curiosity, but would they understand they were employing their curiosity, and why that mattered? In another: after discussing when students had last felt curious, would the instructors simply tell them why that was important, or ask the students to try and work it out themselves? In each instance: what would Josh’s book suggest?

We ended up with four different lesson plans on whiteboards around the classroom, and then sat down in a circle to consider what they’d learned from the exercise. It was hard, someone said. There were a lot of moving parts to try and remember in a lesson plan. Transitions between exercises were something they hadn’t thought about. The meta piece of teaching students why curiosity was important was really difficult. We talked each of these things through.

And then I asked: which methods for harnessing curiosity that Josh talked about did I use to structure this lesson today? Were they curious about what went into a good lesson? Did they feel curious about how things would turn out?

At least one student’s confessed to not being able to think of anything at this point. But that was because they’d all engaged deeply with the reading; they’d all pushed their learning edges; they’d all had to use their smarts to do something other than simply tell me what the book said. They (at least one person begrudgingly) admitted that yes, I’d harnessed their curiosity – that they’d had to bridge the gap between what they knew and what was new to them. And every last one of them did an awesome job.

(I heard one student confess she was going right home to take a nap after class to rest her brain.

Me too.)