What Do Historians Do? (II)

Have you ever asked your students exactly what historians do?

I’m teaching my department’s historiography and research methods course this term, and ‘what do historians do?’ is one of my favorite questions. No one ever asked me to think about this when I was an undergrad. Historians were quasi-mythic creatures who lived Somewhere Else, Doing History Things, and Writing Lots of Books. I knew some of my professors were historians (I was an American Studies undergrad) but other than show up a couple of times a week to lecture, I couldn’t have begun to guess how they spent the rest of their time.

I’m not alone in this befuddlement. In Why Learn History When It’s Already On Your Phone?, Sam Wineburg notes that:

“Many students get their first exposure to history from a textbook. Asked where the book gets its information, children find the question puzzling: the book knows what happened because, well, duh, it’s a history book. When Jeffrey Nokes, a researcher at Brigham Young University, asked elementary schoolchildren what scientists do, most had a germ of an idea: scientists wore lab coats and performed experiments. But historians? Children pictured them ‘surfing Wikipedia, watching the History Channel, or listening to lectures.’ Kids had no clue how historians made knowledge.” (106-107.)

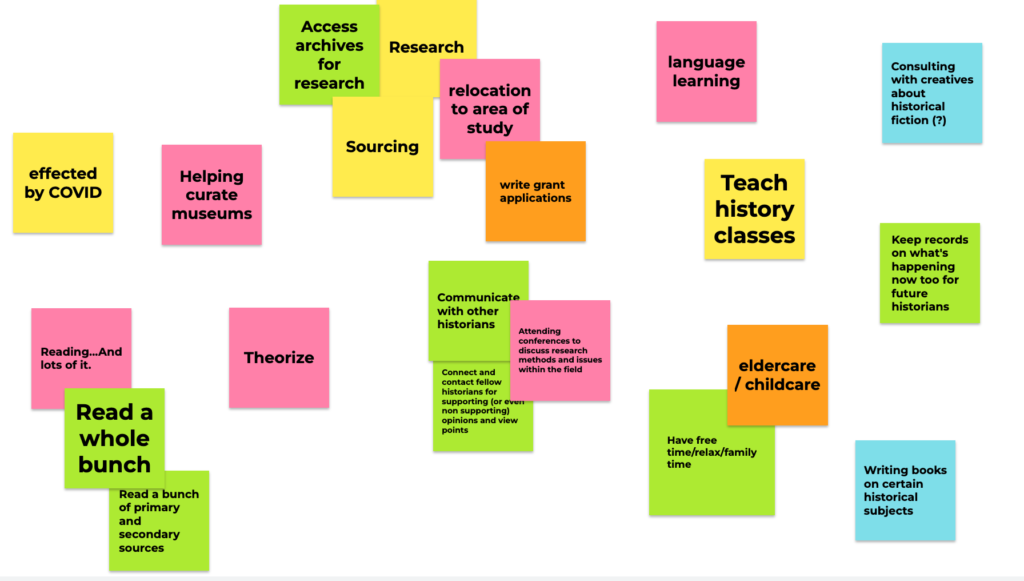

I asked the students in my class what they thought historians do. Here’s what they suggested this term:

[I added the orange post-its about childcare, eldercare, and writing grants.]

My students came up with a pretty good range of things historians might do, but we expanded upon what you see here. I asked them to consider advising and other service work; we talked about precarity and independent research and how many classes someone might be teaching at any one time; we discussed travel, including everything from a daily commute to a long-distance research trip. We talked about how Covid had complicated so many things, and how it had made some things (like conferences) more accessible to more people than before.

I also asked who was doing the laundry, dusting the bookshelves, making dinner, and walking the dog. This was to make a very particular point: the scholarship that the students were reading was the best scholarship that could be produced under very specific circumstances. I always hammer this point home. Historians operate under constraints of time and funding; they have very ordinary lives and have to pay the bills; they cannot live in the archives (even if that was desirable), and they do the best they can to do the best research, writing, and teaching they can but have myriad other responsibilities at home and at work. No work of history can therefore ever be perfect. As so many people have said to me before, perfect is the enemy of done.

Which leads to another reason to ask what historians do. The students are historians. They are doing the best they can under often-challenging circumstances, too.

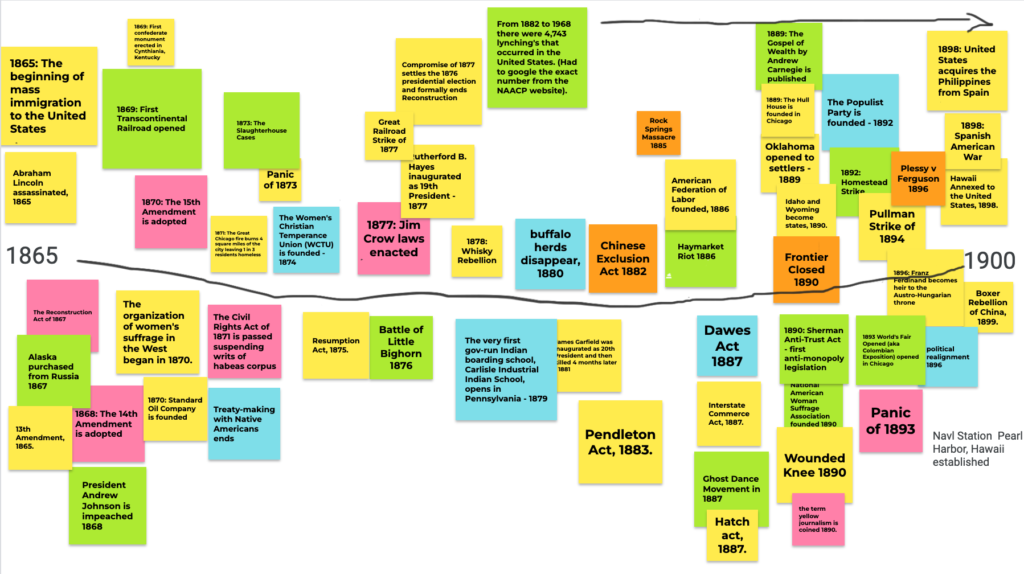

‘What do historians do?” is a question that comes up again and again in the class. My version of this course focuses on the historiography of the U.S West. We start with that old chestnut, Frederick Jackson Turner, and we work our way through the twentieth century until we arrive at today’s scholarship on Indigeneity, gender, class, immigration, and space. We don’t simply tangle with Turner’s scholarship, however. We make a long timeline stretching from 1865 to 1900 and we research what was going on in his lifetime that might explain what he wrote and when. We read Wilbur Jacobs on Turner as “a master teacher,” and we read Alan Bogue’s reflections on Turner’s hatred of football and the allergies that plagued his wife. We learn that hay fever can alter the trajectory of a career, and that white supremacy is a hell of a drug. All of this helps us understand who Turner was, which in turn helps us understand why he argued what he did.

And this, in turn, helps my students start to understand why they make the arguments that they do.

We fill out social identity charts and discuss our experiences of privilege and oppression. We read about standardized testing, and the educational policies made by people who are not teachers, and we analyze the way they were taught history in school. We think about major turning points in their lives—presidential elections, school shootings, political activism—and they read a short piece about why I think I turned out as I did.

They then write their autobiography as a historian, and oh, what a joy those are to read.

Asking what historians do is a practical question, but it’s existential too. What do we do? What use are we? Why does the world need history majors (and lit majors and studio art majors and creative writing majors and music majors and . . .)? What makes history tick? Why can we all look at the same set of documents and yet come up with as many interpretations of those documents as there are people in a room? Why does it matter that we know that will always be the case?

It’s a delight to ask what historians do, and to keep asking and answering and adding and subtracting from the things we think we know.

Have you asked someone lately what it is, exactly, that historians do?