My Autobiograpy as a Historian

Twelve

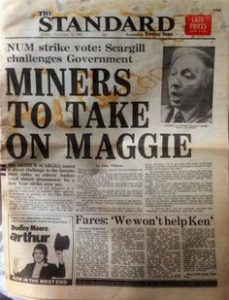

I’m twelve years old, on the top deck of a double-decker bus, riding into the city with my younger brother and mum. As we get close to our destination, I see a squat brick building that we’ve passed many times before without me paying it much attention. Today, however, there’s a line of people spilling out its front door and far down the street. I ask my mum what’s going on.

“It’s a soup kitchen for the miners,” she tells me. “They’re starving.”

I’m appalled. I know the miners’ strike is happening; I know that Margaret Thatcher is trying to break the unions. I’ve watched the news with my parents – the strike is everywhere, on every channel, in every newspaper. Thatcher knows, I realize, that this is happening. And she doesn’t care.

I don’t know about class or power or structural inequality when I’m twelve, but I do know that my family is very much like the miners’ families, and that if Thatcher doesn’t care about them then she doesn’t care about me. And I can feel in my bones that she’s wrong not to care; she’s deeply, wholly, thoroughly wrong.

Nineteen

An odd thing has been happening in my classes at the university. The professors, who are almost all men, only talk about men in lecture. The books we read are written by men and only talk about men, too. I am utterly baffled by this. Where are the women? Logic tells me they existed, but my history books do not.

I go to the university bookstore and I browse the shelves. I find In Search Of Our Mothers’ Gardens by Alice Walker and I buy it because it’s clear it’s about women. In those pages I find the history I’ve been looking for, and words for things I’ve experienced but haven’t been able to describe. I share the book with all of my friends, and we pass it around between us in wonder.

The professor who teaches a course on colonial New England assigns Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s Good Wives for us to read. He opens discussion with, “Well, this is just pots and pans history, isn’t it?” I’m a first-year student, so I don’t object.

Twenty

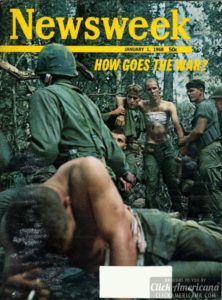

My friend Charlotte and I discover, hidden away in a rarely-visited corner of the library, a treasure trove of Life and Time and Newsweek magazines from the 1960s. We gather handfuls of them and take them to the table that we’ve mentally claimed as ours for the year, spreading them out in front of us. A lot of them are about Vietnam, and the young men looking out from the pages of the magazine are exactly the same age as us.

I flip through the pages and I try to imagine what it would be like to be told I was going to war the next day, or the day after that. I can’t take it in except in as much as my heart hurts and I feel for these people, separated from me by thirty years. The past isn’t dead to me; the past is vibrant and present in that space between Charlotte and I, the magazines, and the table.

Twenty-One

I’m in a class about the African-American Civil Rights Movement. For homework, we’ve all read a document from Eyes on the Prize in which Martin Luther King, Jr. talks about the needs of young, unemployed, single, black men in Chicago in 1967. I lean over to Charlotte and whisper, “What about the young, unemployed, single, black women in Chicago?”

She gives me a knowing look, and immediately it’s like we’re children in church trying to stifle laughter. The professor notices – it’s a small seminar with ten other students – and asks me if there’s anything I’d like to share with the class.

I’ve changed a lot since my first year. I’ve lived abroad for three months; I’ve tracked down more and more books about women and gender; I have the vocabulary to state my case and anger to fuel my words. “What about the young, unemployed, black single women in Chicago?” I ask.

My professor picks up Eyes on the Prize and throws it at my head. I duck and he misses. “I teach one minority group already,” he says. “I don’t have to teach any more.”

Twenty-Three

I’m a teaching assistant in an American Indian History class at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. It’s a month since my own graduation with a BA, and now I’m teaching students things that I only really understand because I read the book a week before they do.

Someone asks a question. I try to answer, but get something wrong, and another student points this out. I thank them and say, I don’t know about that part of things, but I will find out.

The student nods, satisfied, and I realize, oh my god, I love this. I love teaching. I love college students. I love making complex subjects understandable. I want to do this forever.

—–

So I do.

That phrase masks the weight of a multitude of experiences – GRE exams, financial pressures, students questioning grades, difficult classes, grant proposals, research trips that scare me half to death, the challenges of my own mental health, and four years spent passionately pursuing political activism on the side. I interview for the job I will eventually hold at the AHA in Seattle and can only go because my friends pool their money to pay for my hotel room, and another friend gifts me with enough frequent flyer miles to get there. When the time comes, I struggle to afford the weighted paper on which the graduate college expects me to print my dissertation.

But I write, and I carry Alice Walker with me. I research, and I look for the women who matter so much but who left so little behind. I teach, and I try to convey what it is to be twenty in 1648, and 1776, and 1830, and all the years between. When my students ask questions I remind myself it is my job to be wholly unlike my own professors, so I say “I don’t know” and I find things out.

I teach my students that there is no such thing as objectivity – that we are all the sum of the influential events in our lives, and I ask them to write their autobiography as a historian, to winnow out the things that shape how they approach the past.

And then it’s summer, and I write my own autobiography, and I smile to think of the books in my office, weighing down shelves with all the stories my professors never thought to teach.

I’ve replaced those historians now. And it feels so very good.

2 thoughts on “My Autobiograpy as a Historian”

Beautiful Cath. I remember you at 10 years old. I admired you then for your thirst of knowledge. How you have grown. It’s been a long time since I have seen you but your journey is incredible, one day I’d love to share a bottle of wine with you and catch up. Keep shining the light and being a great example.

Thank you for being a woman who has left so much behind.

Much love across the pond!

Mary

Thank you, love!