The Hamilton Exhibition

Warning: spoilers ahead for the Hamilton Exhibition, currently in Chicago. If you’d prefer to avoid exhibition spoilers, skip this post!

I teach a course called Museums, Monuments, and Memory, where my students study public history theory and build an exhibition (including exhibit architecture) from the ground up in ten weeks. It’s a really fun class. People therefore generally imagine that I love museums.

But actually, I don’t.

There are lots of reasons for this, and I cannot hope to name them all. But too many museums are uncritical repositories of artifacts – and human remains – stolen during colonization. Too many museums strip objects of their cultural context. Too many museums overburden their exhibits with text. Many museums repeat outdated, inaccurate information, and many more are not accessible. And while there are museums that do wonderful jobs at creating exhibitions that catch people up and capture their imagination, far too many do not. I am often bored in museums, and I leave having seen a painting or a book or a letter or a vase while learning almost nothing about it.

Funding streams and political fights over which stories deserve to be told (and how) are often at the root of many of these problems. I understand the challenges so many hard-working museum professionals face.

But I just don’t love museums.

I went to the Hamilton Exhibition today, therefore, wondering what I was getting into. I had some preliminary information. Several friends had already visited it, and reported that it was amazing. I knew there were nineteen galleries, and that David Korins, a Broadway set designer, was one of the people who created those galleries. I knew Joanne Freeman was involved (as was one of the professors at Knox, Michael Hattem). I knew that tickets (I paid $40) were prohibitively expensive for many people (although not as prohibitively expensive as the show). I was prepared to be a skeptic.

But reader, I loved it.

First, the creators have given a lot of thought to accessibility. The exhibition is wheelchair accessible, and there are wheelchairs at the exhibition for use by visitors who might need one and don’t have their own. Visitors who hear without difficulty are given an audio unit and headset as they wait in line to enter the exhibition (the audio plays automatically when you enter a new gallery, and there are lots of audio stations throughout the exhibition that provide opportunities to go more into depth on the issues presented). Transcripts of all the audio segments are available for anyone who’s hard of hearing, and the introductory video is subtitled. The exhibition text is also available in large print for anyone with vision issues.

There are no strobe-effect lights in any of the galleries. Visitors who experience sensory overload from a lot of noise may find the gallery about the national debt and early Republic policy overwhelming, as that gallery is modeled on a carnival/circus, with all the hubbub that entails. The score from Hamilton provides a backdrop to all the galleries, and again, this may be difficult for people with sensory issues. There was very little visitor conversation when I was there, however, as almost everyone was intent on listening to their audio tour. People who use assistive devices to walk may find two low bridges between galleries difficult, as the boards are very bouncy. (I suspect this is meant to suggest the precarity of the new Republic.) There are, however, benches to sit on in several of the galleries.

Second: it’s freaking gorgeous.

This is not an exhibition about artifacts (although you can see things like actual letters from Hamilton and Burr). Instead, it’s a grand piece of storytelling, with the design of each gallery emphasizing key points in the narrative, or distilling a mood.

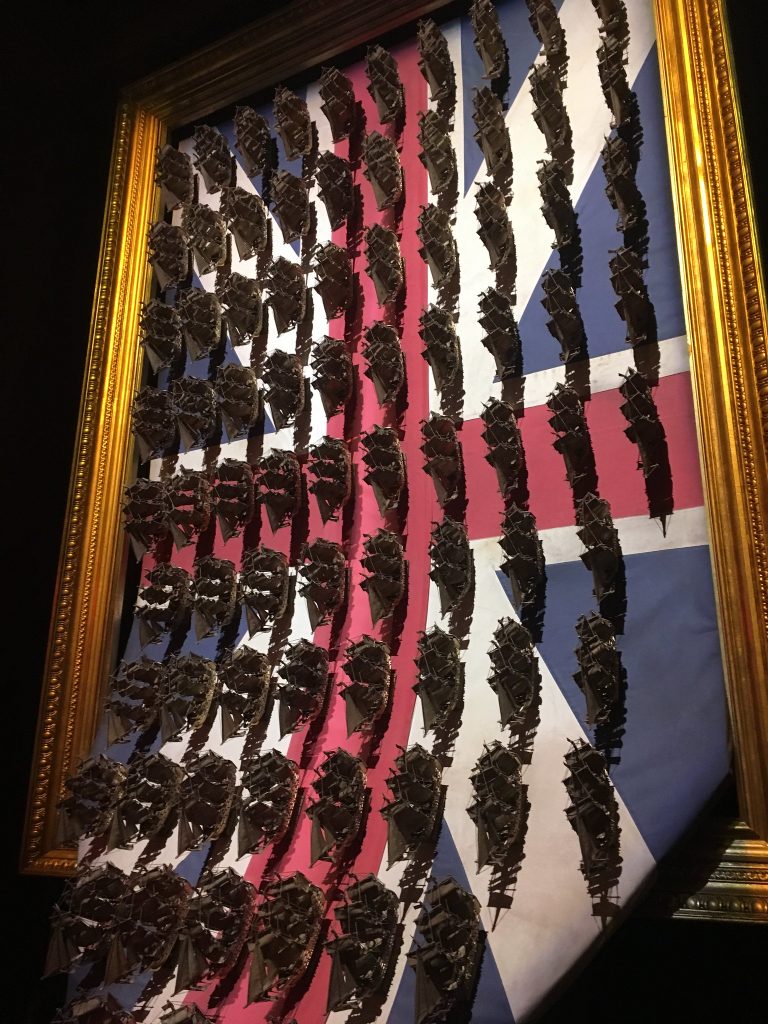

For example, the first gallery looks at the Caribbean in which Hamilton grew up, the enslaved labor that sustained his job as a teenage clerk, and the whole society and economic system that surrounded him. Hamilton was poor – and that’s summed up by a massive set of scales in the middle of the room that demonstrates that a half-barrel of sugar was worth more than Hamilton’s bed, bedclothes, and all the books he owned. But Hamilton was also free and white, and the gallery carefully details – through text, audio, and visuals – that the forced migration of enslaved Africans to the region was theft, that enslaved people came from all statuses in their home communities and practiced multiple professions, and that slavery was wholly inhumane. There’s also a massive map on the far wall of the gallery that shows enslavement, migration, settler colonialism, and trade between Africa, the Americas, and Europe, and does a good job of imparting the massive scale of the slave trade.

In terms of mood, one of the galleries that I enjoyed the most focused on the hurricane Hamilton survived before emigrating to North America. The entire gallery consists of a round room, with a gently inclining pathway, built around a revolving interpretation of the physicality of the hurricane. The whole room is bathed in blue light. The installation consists of trunks, books, broken beds, tables, chairs, and other detritus caught up in the storm. In the audio that accompanies the installation, Lin-Manuel Miranda reads from the letter Hamilton wrote describing the hurricane. And all of this, if you’ve seen the show, is beautifully evocative of the song ‘Hurricane’ and the astonishing accompanying choreography.

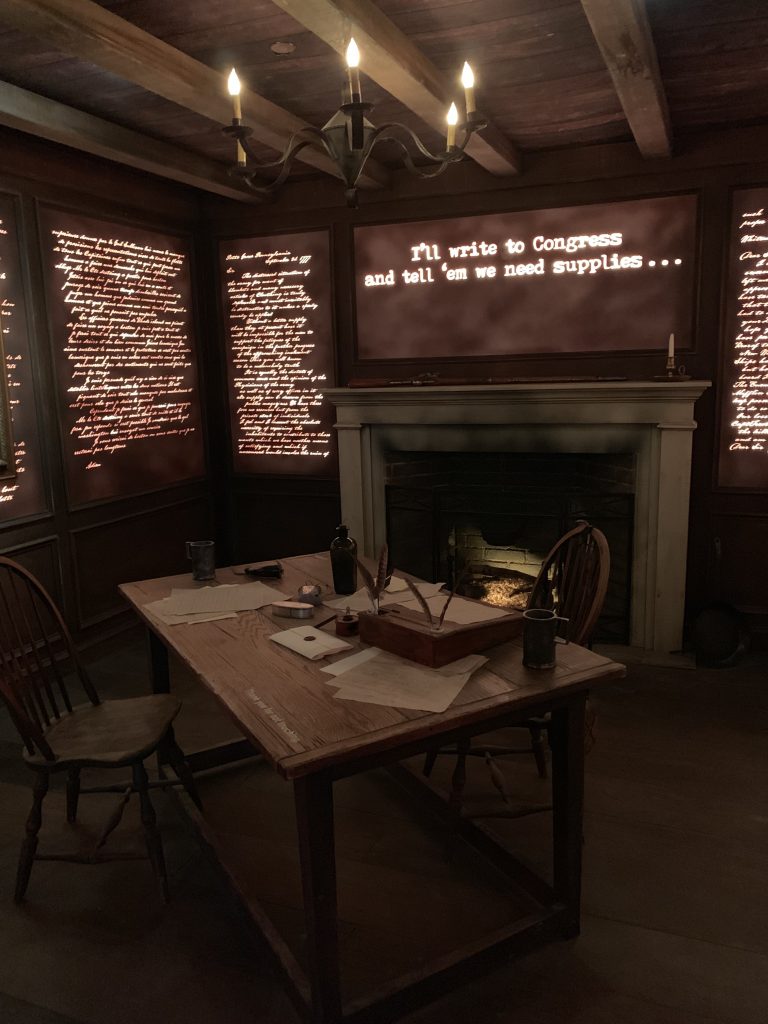

There are many moments like this. There’s a (gentle) gangplank you walk down to enter a gallery about the events that came before the Revolutionary War so that you can experience arriving in (a version of) New York much as Hamilton (the character) does in the musical. There’s a room that focuses on Hamilton as an aide to Washington during the war, with a desk surrounded by walls lit up by line after line of Hamilton’s handwriting. There is the set-up of a mythical ball, where you can go from guest to guest learning more about each person and their relationship to the war.

And then there’s the battle tent in the middle of the exhibition where you learn about the battle of Yorktown from a tech table that doubles as both a shifting map and a chess table with key Revolutionary figures moving on and off the board. (I believe that’s around the time I said “holy fuck!” to myself.)

Since I know the history of the period, I didn’t listen to every audio station in the exhibition, so I cannot guarantee there isn’t misinformation somewhere. I did find the audio about Native people in the 1780s severely lacking, weighed down with vast simplifications about things like the fur tade, a pervasive sense of doom, and the suggestion that by 1800 resistance to settler colonists was over. Um, no. (Try reading this instead, or this, or this.)

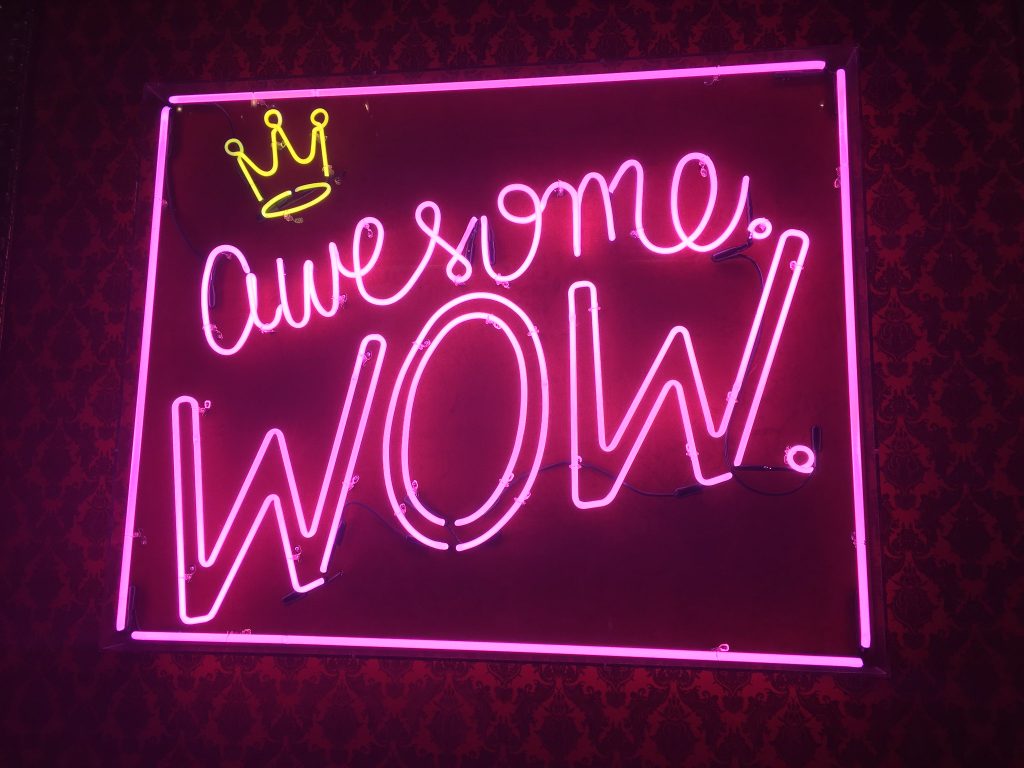

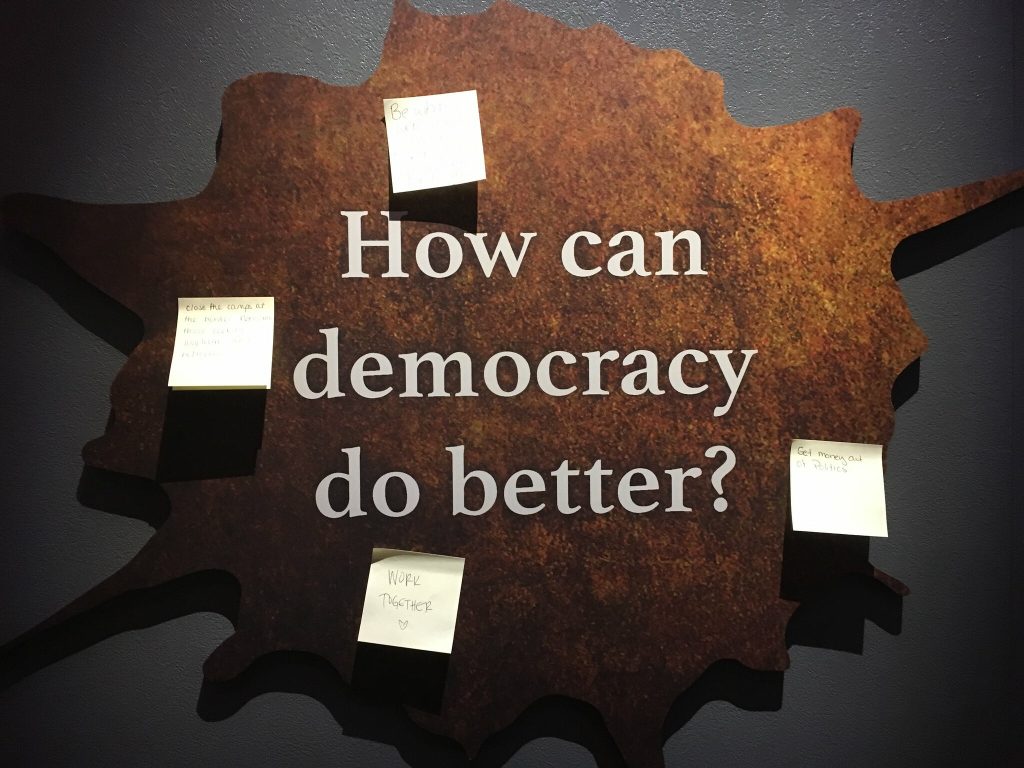

The last room in the exhibition focuses on Eliza Hamiton’s efforts to tell Alexander Hamilton’s story, complete with the score from the final song in the musical. The ceiling features an incredible winding scroll of Hamilton’s writing that absolutely captivated me. There’s also an area for visitors to add to the story the exhibition tells by writing their hopes for America on a post-it note and fixing it to the wall. I went early in the day, so there were very few notes there, and I was relieved that none were politically hostile. (I wrote that we should close the camps and welcome asylum seekers and refugees.) It was a thoughtful transitional moment between the exhibition and the outside world – or at least between the exhibition and the gift shop, into which you step as soon as you’re done.

The gift shop is overpriced. The café is about as expensive as any café in downtown Chicago. The bathrooms are clean and attractive. Please don’t do what I did and miss that there are free trolleys that run between the Soldier Field and Adler Planetarium parking lots and the exhibition. You, like me, will only end up walking an extra twenty minutes and showing up attractively dripping with sweat. The exhibition is air-conditioned, so at least by the time you take a selfie at the end, you’ll look a little less bedraggled.

I’m not sure this review can do justice to how much I enjoyed myself, how astonishing an achievement the exhibition is, or how moving I found the relationship between the audio guide, the ambient score, the text, and the set design. I’ll just say this – if you have the opportunity and means to go see this exhibition before it moves in September, do. And my experience suggests that going on a weekday morning is a good way to avoid the crowds.

Now excuse me, as I have a pressing appointment with the Hamilton soundtrack.