For Those of Us Who Do Not Love the Archives

I’m in the middle of an extended research trip to Philadelphia, where I’m working as a short-term fellow in the library of the American Philosophical Society. The APS is a wonder – the staff have been unfailingly generous and kind; the library itself is beautiful; the sources are abundant. And yet I’m struggling.

We don’t often talk about the realities of archival work. I could line up article after article talking about the difficulties of teaching, one of the three sectors of a typical professor’s job, no matter the institution they’re at. But few of us admit that working in the archives is hard. It’s a professional given that we all love it, otherwise we wouldn’t be historians, right?

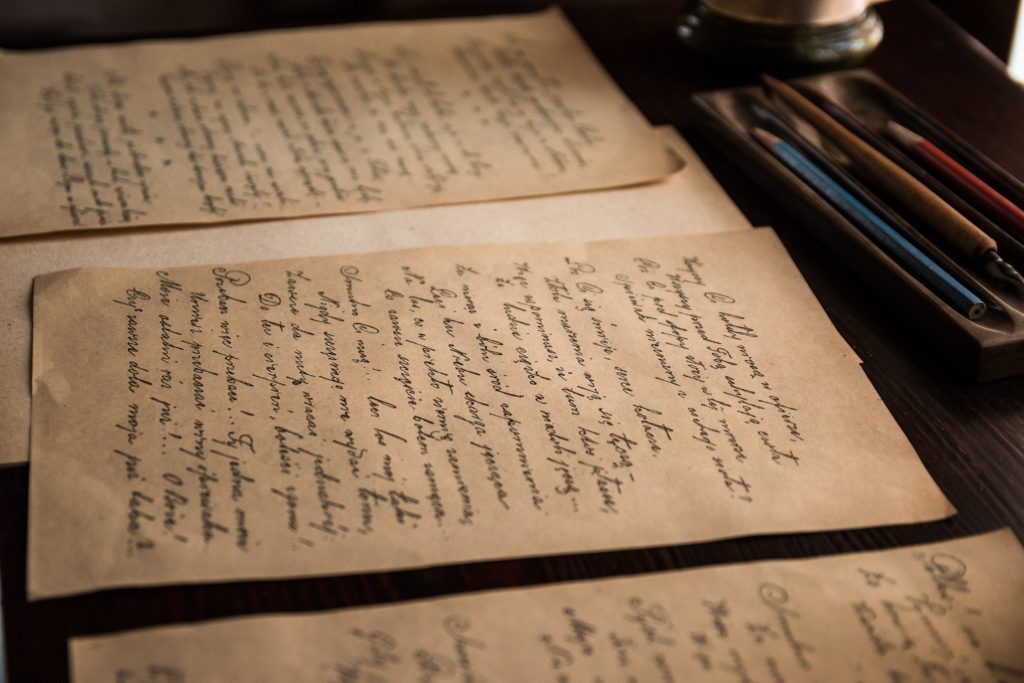

But archival work is lonely work. I’ve been lucky at the APS – there are brown-bag lunches once a week, there was a picnic, and there’s a fellows’ happy hour coming up. But still, most of my time is spent alone in the library, in one-way communication with people who are thoroughly dead. Their words and ideas fascinate me, but it takes a particular kind of focus and attention to read them for hour after hour. My brain spins out a hundred other thoughts while I’m sitting there, and I become restless after a while, wanting – craving! – other input. I can manage to read for about four hours, on average, before my brain is full and I have to go do something else. I am not cognitively equipped to do more.

There have always been other people around in every archive I’ve been to, but they, too, are engaged in one-way communication with their own authors, and some days it’s a special kind of difficult to be in a room of other people saying nothing at all. For all intents and purposes, working in the archive means it’s down to me and the dead people, and even on the days where I find something particularly significant in the record, there are few people who can appreciate with me why it’s so special. Significance requires context, and archival work is done almost without context, except for that which we bring with us in our own heads.

When I’m home and writing, my desks are littered with papers and books, primary sources and secondary sources in mingled piles. At the archives, it’s me and a single source at a time. I miss the conversation with other works already published. I am so grateful for the web (which was in its infancy when I first started researching) since it allows me to pull up an article or a blog post and slot what I’m learning into a bigger picture while I’m still in the library. But my work is still ultimately a one-person venture, especially at the beginning of a project when my ideas are not fully formed and my suppositions still need testing and are too new for an article or blog post.

Many of the documents I read are, by virtue of whose records get saved, by people who were dyed-in-the-wool racists and misogynists. That brings its own difficulty. Absorbing their ideas, even to later pull them apart and expose them for their short-sighted, prejudiced thinking, is toxic – I feel grubby after a day spent with them. And many of the authors I read are also self-hating, which is its own challenge to digest for hours at a time.

The detective work of archival searching is something I do with pleasure. Piecing together different ideas and cross-referencing sources gives me tremendous satisfaction. I love telling stories that haven’t yet been told. But while I have colleagues and friends who find this wholly fulfilling, I find it less so. I am constantly homesick. I miss small things – access to a potato masher has been one that’s come up repeatedly on this trip – and large ones (like my own bed). I miss gathering with friends, and bouncing my ideas off them, and hearing what they’re doing, and seeing their kids. I miss community. I miss feeling part of a larger whole. The imagined community of other scholars is not enough for me.

And yet I grit my teeth and keep on working, because the things I’m finding are the building blocks of something else. It is the hardest part of my job. If you have ways of dealing with the difficulties I’ve described here I would love to hear them! My archival work, like so much else, is always a work in progress, and perhaps there are tricks to it that I haven’t considered. I’d love to give new things a try.

One thought on “For Those of Us Who Do Not Love the Archives”

My tactic for archives particularly is to tell the archivists what I’ve found, especially if it’s exciting. It lets me share the emotion but it also has the side effect of sometimes prompting them to suggest other things based on what I’ve found (best) or highlight things in their collection they can big up to others following after me (at minimum). Archivists are a great resource like that, and most of them totally get the ‘isnt this cool/awful/weird?’ reaction their collections provoke. 🙂