A Different View of the U.S. Civil War

In my U.S. survey course this term – Power and inequity in America to 1865 – we’ve made it a priority to ask ourselves whose voices are lifted up and who is erased by the stories we tell about America. We’ve charted the purposeful crafting of a white supremacist society; we’ve examined resistance to the same; we’ve read primary source documents about women and the fluidity of gender; we’ve dived deep into who “We The People” really were; we’ve consistently tried to position ourselves on the interior of the country looking east, instead of on the east coast looking west.

The course ends with the Civil War, and I assigned my students Chapter Fourteen of the American Yawp to read for class. It is, in many ways, a very good summary of the major themes in Civil War history. It also makes no room for Native stories at all.

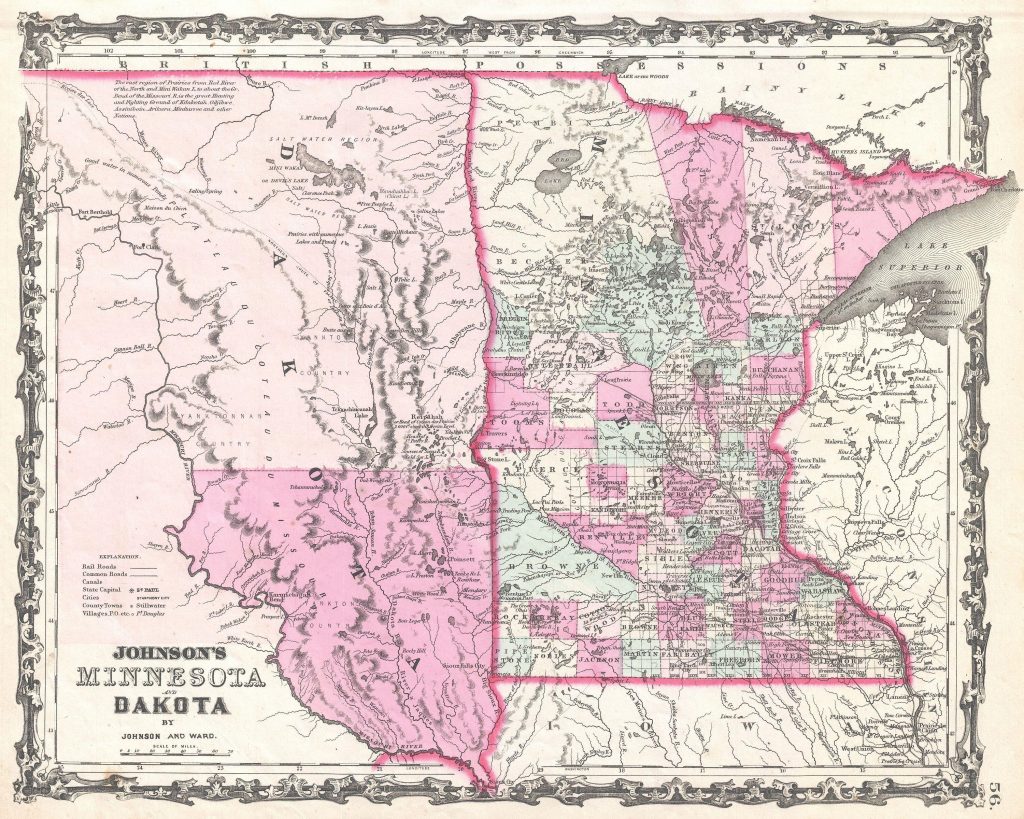

So instead of working with the chapter directly, I came up with a two-class activity to problematize both this view of the Civil War and the periodization that holds the Civil War up as a major watershed for everyone on the continent. In the first class, we collectively listened to Little War on the Prairie, an episode of This American Life that told the story of both the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 and the ways in which that war has been erased from Minnesota memory. I gave my students a stack of post-it notes each, and asked them to write down instances where they saw connections between the show and events we’d previously discussed in class, as well as moments where they saw connections between the show and The American Yawp’s treatment of the Civil War.

The podcast lasts about an hour, and I will confess there was a lot of wriggling and restless shifting in seats going on by the time we were forty minutes in. (When I do this again, I’ll assign the podcast as homework, or encourage the use of the basket of fidget toys I bring to class, as well as let people know ahead of time what we’ll be doing so that they can bring handcrafts to work on while listening if they want.) There was also a lot of writing, however. By the time I stopped the podcast (a few minutes before the end), people had little piles of post-it notes full of observations. I collected those in and kept them until next class.

With about fifteen minutes left in our class period, I asked the students what struck them the most about what they heard. We had a really great discussion about the ways in which the existence of the U.S.-Dakota war was news to most of them; about the ways in which Minnesota has often opted not to wrestle with its own history; and about the lasting effects of the conflict in popular imagination. (Some Minnesota legislators recently voted to reduce funding to the Minnesota Historical Society because MHS changed the name of Historic Fort Snelling to “Fort Snelling at Bdote,” thereby acknowledging the long history of the Dakota people at that place. Members of the Dakota nation have also worked to have the name of a lake in Minneapolis restored to Bde Maka Ska (as opposed to Lake Calhoun), and are fighting lawsuits by local residents who claim the name is too hard to say.)

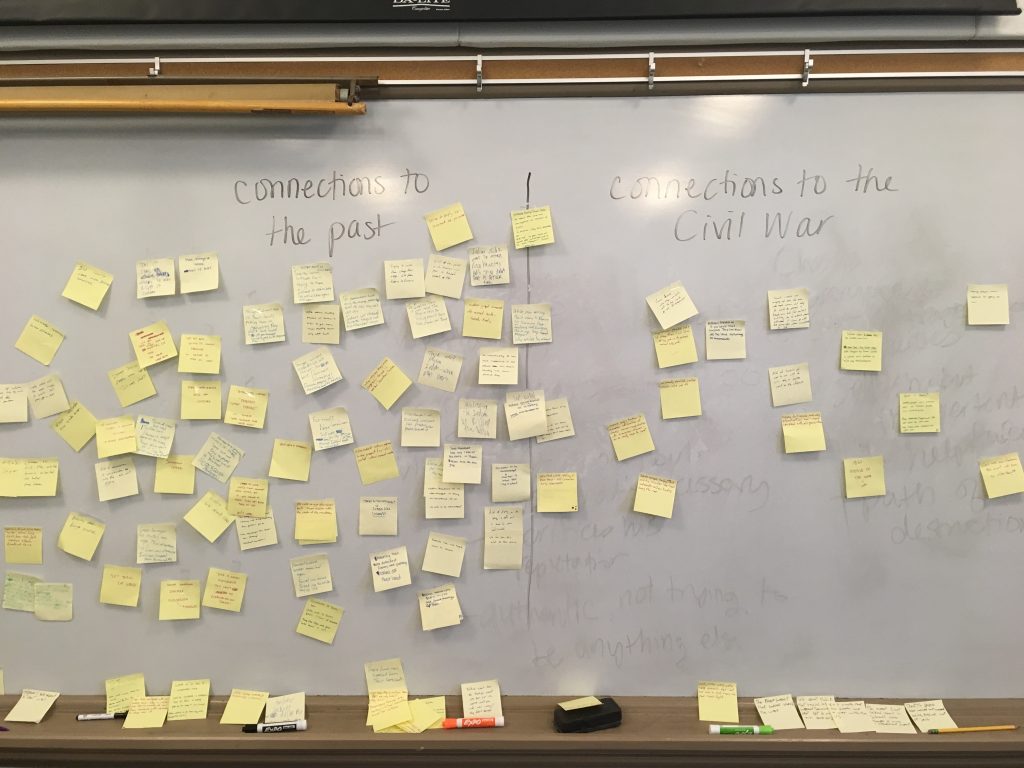

In our second class period, I redistributed everyone’s piles of post-it notes, and drew a line down the center of the whiteboard. On one side I wrote “connections to the past” and on the other “connections to the Civil War.” Students then put their post-its on the side that best fit their observation, clustering like notes with like so that we could see where people had ideas in common.

Everyone made some comment related to the fact that Native history is too often left out of grand narratives about the American past. Students drew connections back to our conversation about The True Story of Pocahontas; to Native people being shipped into Caribbean slavery; to the continued encroachment of non-Native settlers onto Native lands; to the meaning of the Revolution in Indian country; to Henry Knox’s letter to George Washington outlining an assimilationist Indian policy; to Jackson and Removal; to the genocide in California. They also made larger observations about who gets to write history, as well as who gets to teach it and under what conditions. They concluded – to borrow the title of a great book – that you can’t teach U.S. history without American Indians in it.

But we weren’t done. Shifting to a different white board, we drew up a timeline of the “high points” of American history viewed from a traditional lens. We started with Jamestown in 1607; we noted the arrival of the English in New England; we talked about the arrival of enslaved Africans; we put Bacon’s rebellion up on the board, and the Seven Years War, the Revolution, the Constitution . . . you get the idea.

I then asked whether this periodization adequately spoke to the experiences of the majority of the people in early America. They immediately answered no. So to play with that idea, we decided to erase from the timeline things that would be unimportant in a periodization that prioritized Native history. We started earlier, with the great cities of pre-contact America, and we added 1492 for the impact of the disease Columbus brought from Europe. We talked about the Spanish. We kept 1607, but erased 1620 and 1630 because, as one student put it, the key was that the English arrived, not that they kept arriving. We kept the arrival of enslaved Africans because the use of enslaved labor was so central to the project of settler colonialism, because of some enslaved Africans and Native communities cooperated against European colonizers, and because some Native communities possessed African slaves.

Again, you get the idea. (I badly wish I had taken a photo of this timeline, but was so industrious in my cleaning up the classroom for the next class that I erased it before I thought about preserving it. Doh!) We ended up with a timeline that was vastly different to the one we’d created at first, and we discussed why this wasn’t the timeline that most people knew. Who had the power to shape the way we periodize the past? Who had a vested interest in the first timeline, and not the second?

At the conclusion of this discussion, my students were given three more post-it notes, and asked to write down how they’d apply the history they’d learned tomorrow, next week, and within the next year. I loved their answers, and the fact that the exercise communicated that I expected them to keep drawing on what they knew, rather than stowing it away at the end of term, never to be heard from again.

I’ll use this sequence of exercises again when I next teach the survey. I’m especially interested in mucking up the idea that the Civil War had no impact on Native communities, nor Native communities on the Civil War, and will likely add a reading about the western front of the war, or the actions of Civil War generals toward Native people during Reconstruction. And there are so many ways to adapt these activities – to draw up a timeline about African American history, or women’s history, or gender history, for example. I’m going to have a lot of fun playing with the ways I can help my students review their learning at term’s end, and think about its implications for their future.

2 thoughts on “A Different View of the U.S. Civil War”

Always appreciate your designs and writing Cate!