Going Gradeless

It’s been almost five years since I wrote “[Making the Grade],” a blog post about my first venture into ungrading. What felt, at the time, like a truly momentous change turned out to be just the first step in reconceptualizing the role of grading in my courses. After I started ungrading I tweaked things. I rewrote my suggested grading rubric. I finessed the self-evaluation questions. I began to allow all late work to be turned in whenever it was done.

But spring term 2022 was the first term I went all in, going without grades until—in their last assignment—students told me what they thought their course grade should be.

It was amazing.

Doing away with grades crucially didn’t mean doing away with structure, even though people sometimes conflate the two. Here’s what that structure looked like in my classes:

1. We read Alfie Kohn’s “The Case Against Grades” and spent an entire class period (70 minutes) talking about it.

There was a lot in [Kohn’s article] that resonated with my students. They shared their own stories about the physical and mental stress they’d experienced in high school and college, trying to chase not just a grade, but the affirmation and validation they associated with certain numbers and letters. They were up front about the damage this had done to their relationship to learning, and to their relationships with others—the competition the grades generated; the familial approval bestowed or withheld because of them. We discussed motivation—the grade-driven reality of it, the ideal of what they wished it could be, and the complications that came into play given everyone’s unique way of thinking and knowing. They shared grade-related horror stories, and moments where a particular grade had felt great. They also shared their concerns about the idea of doing without grades altogether. It is, as several people articulated, scary to give up a system that you know can be damaging when you also know you can win within it.

I asked the class if they wanted to go gradeless, and explained what this would mean: the regular number of big assignments (three, spread over ten weeks); lots of little ungraded assignments (reading reflections etc); and feedback given at every step of the process. At the end of term they would tell me the grade they thought they should get. I would raise the grade of anyone I thought was undervaluing themself, but otherwise I would respect their decision.

The consensus of the class was to try it. (There were, I discovered when I read the final reflections, two or three people (out of twenty-six) who hadn’t wanted to leap in, but who didn’t feel they could say no. That’s something I’m going to think over during the summer to see if I can’t find a better way to make space for them.)

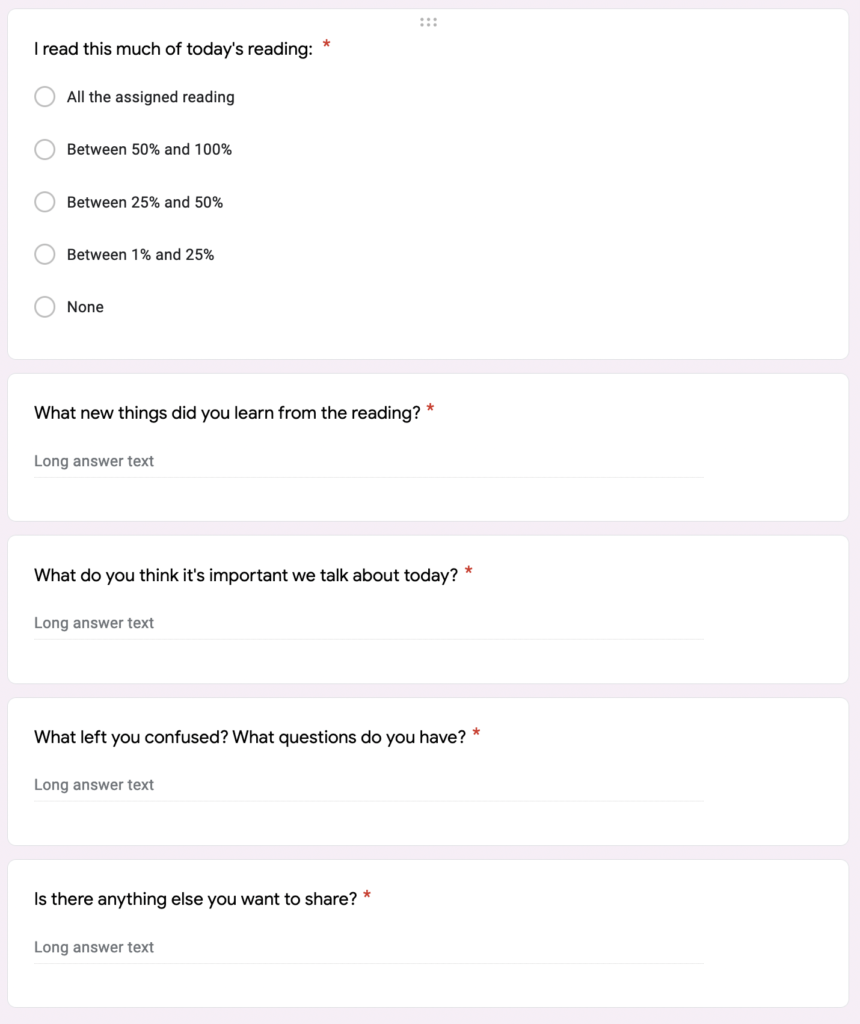

2. There was generally one small ungraded assignment every week, usually a reading reflection in Google forms.

The reading reflections, and the end-of-the-week reflections I sometimes assigned, were a way to gather information about what was inspiring, confusing, or annoying about the readings or activities we did together. Each reading reflection asked how much each student had read of the day’s assigned texts, not so that I could be punitive about the days when people didn’t read as much as I might have hoped, but so that I knew before class what I was dealing with in terms of everyone’s preparation. I did not respond to these reading reflections. Rather, I took the questions people asked, and the things they said they wanted highlighted, and wove them into my lesson plan for the day. There was a feedback loop—the students saw that when they asked a question in the Google form, it got answered in class, or if they expressed that we should really have a conversation about a given topic, we did. This meant the students got to shape the classroom experience, but I didn’t add a stack of grading to my job.

3. There were three big assignments with specific due dates.

I once taught a course where I did away with due dates altogether, since they struck me as arbitrary and perhaps unhelpful. What followed was a cascade failure, where almost everyone wrote both their papers at the last minute and turned them in on the last day of class, hours before a third paper was due in lieu of a final exam. I learned my lesson and on reflection I had to admit that I should have known better; after all, I don’t do well without a schedule myself. In the interim I also read more about neuroatypicality, and the necessity of structure to facilitate some students’ learning. So this time around we had due dates, and though anyone could turn in late work without giving me an explanation, it provided the scaffolding all of us (me included!) needed to do our best.

The first big assignment was to write a letter to anyone the student wanted (including fictional characters), telling them about something they’d learned in class that they thought was really important, and why. This is my sneaky way of getting my students to write like historians—to make an argument, to marshal evidence, and to analyze texts—since so many people show up in my classes convinced they can’t write. The letter demonstrates that they very much can if I can help them think outside the box of what a “paper” is supposed to be. Once those papers came in, everyone sat down with me for a fifteen-minute conversation where we talked about what was easy about the assignment, and what was hard, and why. No two conversations were alike, and that was invigorating.

(I scheduled time on my calendar for these conversations the week that the letters were due, but also the week after. This is, I’ve found, key to making room for late work—to plan so that I know I will be responding to student work over a two or three-week period, a little at a time.)

The second big assignment was an unessay on any topic related to the class that the student wanted. I set aside time every week for us to work on those projects—for people to do library research; for people to read; for people to write or paint or sculpt; for people to talk with me about their projects. The final feedback students got came in the form of a class period devoted to several rounds of a gallery walk, with students taking turns to go look at other people’s projects, or to stand and talk about their own. It was a festival of creativity and fun and new information, with the opportunity for people to ask lots of questions and others to offer thoughtful answers. I mingled with everyone else, asked my questions, and listened to what students told each other. It was invigorating.

The final big assignment, due at the very end of exams, was to reflect on the term. Students could turn this reflection in as audio, video, or as a letter to me, and were welcome to reflect in any way that felt meaningful. (I provided several questions to consider for those who needed structure.)

The reflections were a revelation. Everyone took them seriously, and provided an analysis of their own strengths—and the challenges they’d faced—that I could never have produced as an external evaluator. Each reflection was unique. Some students shared some of the personal struggles they’d faced; some focused entirely on what we’d read; some identified a particular conversation as a personal turning point; everyone was fair and honest about themselves and what their priorities had been. Some students struggled to suggest a grade for themselves, but everyone did, and they were pretty much exactly where I would have put them if I had graded them myself. I raised a few grades, but no one claimed anything that was inappropriately high. More than one student explicitly said that they found value in reflecting on the entire ten weeks of class, and wished more classes asked them to do so.

I’ll need to adapt this system for fall when I’m teaching an upper-level research seminar. There students only have one, term-length assignment, so I’m going to give some thought to how to structure things to provide more scaffolding, some incremental due dates, and an opportunity to reflect honestly on their work. But I am 100% sold on this way of doing things. I’m sure I will tinker with the method, just as I did when I first ventured into ungrading, but that’s part of the delight of this for me—to get a meaningful read on what’s working and what’s not directly from the students, and to have them bequeath their insights to the students who come after them.