Making the First Day Matter

In my lower-level classes, many of my students have little idea what it means to be a practicing historian. Their experience of history has been to read a dry textbook, believing that the god of history has decanted facts onto the page, and to take a lot of quizzes about specific people and events. This is contrary to everything I want them to get out of a history course – I want them to be historians for the duration of the term; to recognize that history is a human creation, to analyze primary sources, to question secondary sources, and to put everything together to come up with arguments and stories of their own.

It follows that one of my favorite first-day activities is to put my students in groups and have them tell a story based on primary sources they’re unlikely to have seen before.

This is a rough-and-tumble first day activity. I purposefully don’t tell my students how to analyze the documents and images. Instead I put them in randomized groups, ask them to put the sources in the order that makes the most sense to them, and tell the story the sources supply. They can start with “Once Upon a Time . . . “ if that helps.

I have two go-to document packets. One contains sources from the American Revolutionary era, and one sources from the Cuban Missile crisis. Whether I’m teaching early or contemporary America, or U.S. or world history, the packets relate to events and ideas we’ll reference during the course.*

[eta 1/9/19: more primary source packets on European history are now available [at this post]]

The packets of sources I distribute are purposefully doctored. While everyone receives all the images, for example, only certain groups will get a written document that adds new information to mix. In the case of the Revolutionary sources, one group receives a letter from Abigail to John Adams complaining about women’s political rights. In the Cuban Missile Crisis packet, one group will get a letter from Castro to Krushchev, articulating Castro’s hopes for how the crisis will play out. These documents help me make a point later in the lesson.

After about 15-20 minutes, I have everyone come back together and read their story aloud. This is generally fun – the stories are very different; one or two groups always have someone in the mix who knows a lot about the era in question and fills in a lot of blanks; another group will decide to take the most ridiculous approach possible in the hopes of making everyone laugh. There are lots of stories that fall in between. In doing this exercise multiple times a year, every year, I’ve never had two stories be alike.

And that’s the point. After all the stories have been read aloud, I ask the class to explain why the stories are so different. After all, everyone had the same sources, so why such different narratives? There are several answers that generally surface:

- Different amounts of prior knowledge about the subject

- Different educational backgrounds

- Different cultural experiences

- Different questions asked of the sources

- Different levels of experience with analyzing sources

- The ability (or lack thereof) to cross-reference with other sources

- Different ways of appealing to an audience

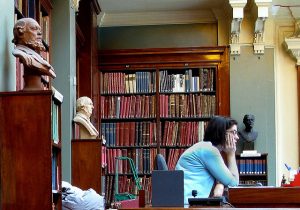

Somewhere in this discussion, someone will point out that one group had an extra source. This becomes a wonderful way to talk about preservation and access issues as they relate to libraries and archives. Who produced the sources we examined? Who had the leisure or business time to do so? Why did a library or archive decide they should be saved? Who has access to that library or archive? What happens if you can’t find the voices of a key group of people – lower class individuals, women, the illiterate, or groups from various ethnic and racial backgrounds? How does the story change?

This, I wrap up by saying, is what historians do – we gather all the sources we can and search for the story they tell us as individuals of varying social identities, privileges, and experiences. Historians regularly disagree; no one historian has the last word. History changes as more sources are found, old ones are reexamined, and new theories suggest new interpretive frameworks. For the duration of the term, every student in the class will be a working historian, putting sources together to understand one part of our collective past.

This exercise sets the tone for what we’ll be doing for the rest of the term. It’s one way to use the first day of class productively, and it’s usually really fun. That history need not be an enterprise done in isolation, without humor, while requiring rote memorization is a great lesson in and of itself.

* I first put these packets together to use with K-12 history teachers enrolled in Bringing History Home, an Iowa-based program in curriculum development funded by three successive Teaching American History grants. For more on this program go to http://www.bringinghistoryhome.org.

5 thoughts on “Making the First Day Matter”

Thank you Cate!

Excited to use this first-day exercise. Thank you for bringing the primary source resource packets together.

Best,

Laura